Mischief Afoot: Vans Kicks MSCHF’s Main Defense to Trademark Infringement to the Curb in Art Sneaker Dispute

If the shoe fits, wear it. Or so the Second Circuit mused in a recent decision, in which it “re-boxed” an art collective’s appeal challenging a preliminary injunction that barred further sales of a limited-edition art sneaker. In its decision, the appeals court relied on the recent Supreme Court Jack Daniel’s trademark decision that found works cannot qualify for increased First Amendment protection as “expressive works” for purposes of the Rogers test when they make unauthorized use of others’ trademarks for source identification purposes. (Vans, Inc. v. MSCHF Product Studio, Inc., 88 F.4th 125 (2d Cir. 2023)).

MSCHF Product Studio, Inc. (“MSCHF”) is a Brooklyn-based anti-establishment art collective that uses artwork as commentary that tries “to start a conversation about consumer culture…by participating in consumer culture.” To this aim, MSCHF has produced a variety of limited edition products, including prior sneaker collaborations with music artists and a work of art called “The Persistence of Chaos” consisting of a laptop infected with six computer viruses and other historical malware (that sold at auction for more than $1.3 million). MSCHF ordinarily produces limited quantities of its products and sells them during prescribed sales periods (or “drops”).

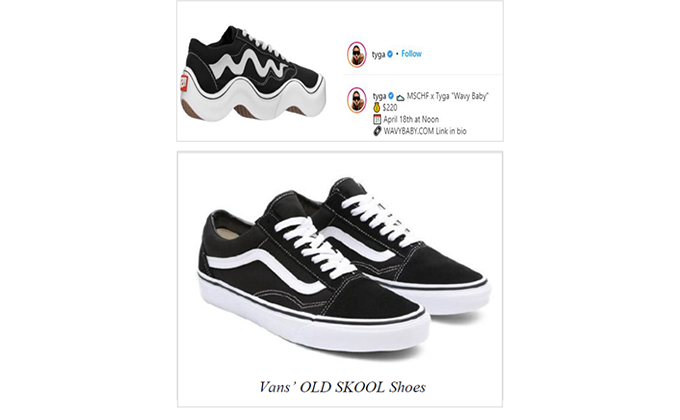

MSCHF piqued Vans’ attention in early 2022 after they announced the “Wavy Baby” sneaker release, which they collaborated with rapper Tyga to create, promote and sell. By their own admission, MSCHF modeled the Wavy Baby after the “most iconic, prototypical” skate shoe: the Vans “Old Skool.”

[See below images comparing the two sneakers].

MSCHF scheduled the Wavy Baby drop for April 18, 2022, and began promoting the shoes in collaboration with Tyga. In response, Vans promptly sent both MSCHF and Tyga cease and desist letters, which were ignored. Vans then put its foot down and filed a complaint on April 14, 2022, requesting, among other things, injunctive relief blocking the Wavy Baby release, as Vans perceived the shoes to be infringing various trademarks related to the Old Skool sneaker.

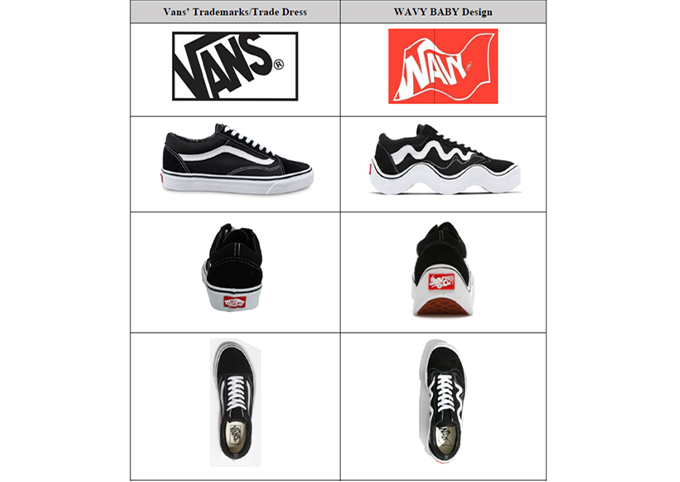

[See the following image comparing the design of both sneakers].

Vans subsequently filed a motion for a temporary restraining order and a preliminary injunction, in which it asked the district court to enjoin MSCHF from: releasing the shoes for sale; fulfilling orders for the shoes; using Vans’ Old Skool trade dress, marks, or confusingly similar marks; and from using any such marks in any advertising, marketing or promotion. Unwilling to wait, MSCHF proceeded with the Wavy Baby drop as scheduled and purportedly sold all 4,306 pieces of the limited-edition Wavy Baby art shoes in one hour. MSCHF then filed opposition papers to Vans’ motion that stated, based on the response it had gotten from buyers and interested fans, it was not “aware of any collector who bought or tried to buy a Wavy Baby and thought they were buying a Vans shoe.”

A New York district court quickly laced up and granted Vans’ request for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction barring MSCHF from fulfilling orders for the Wavy Baby shoes and essentially freezing its revenues from the Wavy Baby, among other relief. The lower court found that Vans had presented enough evidence of consumer confusion and had therefore shown a likelihood of success on its trademark claims. Further, the court rejected MSCHF’s First Amendment defense and concluded that the shoes failed to meet the requirements for a successful parody because “the Wavy Baby shoes and packaging in and of themselves fail to convey the satirical message.” Wanting to put the shoe on the other foot, MSCHF appealed to the Second Circuit. In its appeal MSCHF argued that Vans’ claims were precluded by the First Amendment.

The primary function of a trademark is to identify the source of goods or services, which is important, in part, because it enables consumers to make informed purchasing decisions. Per the Supreme Court, the “cardinal sin” under trademark law is thus to “confuse consumers about source — to make (some of) them think that one producer’s products are another’s.” Befitting that, in federal trademark infringement cases brought under the Lanham Act, courts generally use a multifactor test to make an inquiry into the allegedly infringing trademark use and whether the defendant’s actions are “likely to cause confusion” or otherwise cause mistake or deceive as to the affiliation, connection or association of the defendant's goods or services with those of the plaintiff.

As the Second Circuit noted, the traditional consumer confusion inquiry may be applied more narrowly if the allegedly infringing good or service is a work of "artistic expression." Under the Rogers test (derived from a 1989 Second Circuit decision, which has been widely adopted in other circuits), the Lanham Act and the accompanying multifactor infringement analysis will apply to artistic works only where the public interest in avoiding consumer confusion outweighs the public interest in free expression. Thus, the Rogers precedent states that the Lanham Act should not apply to "artistic works" as long as the defendant's use of the mark is (1) artistically relevant to the work, and (2) not "explicitly misleading" as to the source or content of the work. In arguing that it was entitled to the heightened First Amendment protections of the Rogers test, MSCHF in essence asserted that the Wavy Baby sneakers are expressive works and that it did not use the Vans marks to designate the shoe’s source but solely to perform another expressive function.

The natural question arising from this assertion is how an expressive work is defined. In hearing the appeal, the Second Circuit was faced with the core issue of “whether and when an alleged infringer who uses another’s trademark for parodic purposes is entitled to heightened First Amendment protections, rather than the Lanham Act’s traditional likelihood of confusion inquiry.” To decide this issue, the appellate court looked to a recent Supreme Court ruling in Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC, 143 S.Ct. 1578 (2023). In that case, VIP Products created a plush dog toy called “Bad Spaniels” (a play on “Jack Daniel’s”) that was designed to look like a Jack Daniel’s whiskey bottle, but with a variety of dog-related changes. Jack Daniel’s alleged the dog toys infringed its trademarks and the case made its way up to the Supreme Court.

Like MSCHF, VIP Products argued that its use of the Jack Daniel’s trademarks was entitled to review under the Rogers test and therefore the Court should sideline the likelihood of confusion test. The Supreme Court disagreed, holding that VIP Products used the trademarks as trademarks, that is, to identify the source of its own products. Although the Court acknowledged that parodies are inherently expressive, it held that when an alleged infringer uses a trademark as a designation of source for the infringer's own goods, the Rogers test does not apply (though, the Court acknowledged that even if Rogers was inapplicable, VIP Product’s parodic efforts might be relevant in a standard trademark analysis).

The Second Circuit held that “MSCHF used Vans' marks in much the same way that VIP Products used Jack Daniel's marks — as source identifiers” and highlighted several ways that MSCHF’s design evoked elements of trademarks and trade dress from Vans’ Old Skool shoes, including the classic black and white color scheme, the side stripe, the perforated soles, the logo on the heel and footbed, and the packaging. The court therefore concluded that MSCHF used these elements as designation of source and, relying on the SCOTUS opinion, that MSCHF was not entitled to the heightened review under the Rogers test. The court clarified, “even if a defendant uses a mark to parody the trademark holder’s product, Rogers does not apply if the mark is used ‘at least in part for source identification.’” In other words, Vans would have been well within its rights to pour a celebratory shot of Jack as MSCHF’s most prominent defense had been rejected on appeal.

After determining that the district court did not err in declining to apply the Rogers test, the Second Circuit had the task of deciding whether the district court erred in its traditional consumer confusion analysis. The likelihood of confusion test involves a balancing test of eight factors, which the Second Circuit used to affirm the lower court’s finding that Vans was likely to prevail on the merits of its infringement claim.

The Second Circuit was ultimately unimpressed by MSCHF’s mischief and kicked off its main defenses. More broadly, this case serves as an example of how the Supreme Court’s Jack Daniel’s precedent affects the Rogers analysis in other types of fact patterns and disputes. With MSCHF blocked from selling any additional Wavy Baby’s, sneakerheads and art collectors looking for "wobbly, and unbalanced” skate shoe artworks (along with the accompanying MSCHF manifesto on consumer culture) will have to check the secondary markets.

In the meantime, the court docket in the case shows that, as of a March 2024 telephone conference with the court, the parties are exploring a possible settlement – especially since MSCHF’s petition to the Supreme Court requesting review the Second Circuit’s decision was denied on procedural grounds.