November 2024 AFRs and 7520 Rate

The November 2024 Section 7520 rate for use with estate planning techniques such as CRTs, CLTs, QPRTs and GRATs is 4.40%, which was the same as the October 2024 rate. The November applicable federal rate (“AFR”) for use with a sale to a defective grantor trust or intra-family loan with a note having a duration of:

- 3 years or less (the short-term rate, compounded annually) is 4.00%, down from 4.21% in October;

- 3 to 9 years (the mid-term rate, compounded annually) is 3.70%, which remained the same as the October rate; and

- 9 years or more (the long-term rate, compounded annually) is 4.15%, up from 4.10% in October.

Inflation Adjustments for 2025 & Planning Considerations

| 2025 | 2024 | Increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime Federal Estate/Gift Tax Exemption | $13,990,000 | $13,610,000 | $380,000 |

| Annual Exclusion for Gifts | $19,000 | $18,000 | $1,000 |

| Beginning of Highest Income Tax Bracket or T&E | $15,650 | $15,520 | $450 |

| Annual Exclusion for Gifts to non-Citizen Spouse | $190,000 | $185,000 | $5,000 |

- Planning Considerations for 2025: “Use it, or Lose it”

- Encourage Lifetime Gifting Early

- Gift early – lawyers, appraisers, financial advisors, etc. will all be extremely busy during this time.

- Consider gifting easier-to-value assets due to time pressures.

- Look to allocate GST exemption to existing trusts.

- Leveraging SLATs before the sunset.

- Encourage Lifetime Gifting Early

Delaware “Beneficiary Well-Being Trust” [1]

Overview:

On August 29, 2024, Delaware enacted a new “Beneficiary Well-Being Trust” opt-in statute. The Beneficiary Well-Being Trust (hereinafter referred to as the “BWT”) is designed to address a Settlor’s concerns related to the holistic well-being of beneficiaries beyond simple financial support.

The BWT sets out to accomplish this goal by implementing well-being language in the governing instrument based on research from positive psychology and well-being science to broaden the scope to include subjective criteria contributing to a beneficiary’s quality of life. Specifically, by enabling the Trustee to consider factors such as emotional well-being, life satisfaction, and personal development. The trust can be particularly beneficial in cases where the Settlor wishes to ensure that beneficiaries receive support tailored to their personal circumstances.

How it Works – Statutory Provisions:

- 3345(a) – Reference the Statute: The governing instrument must make express reference to § 3345 or any of its sections. Once the governing instrument does this, the language in § 3345 applies and the trust is deemed to include the powers, duties, rights and interests of the Trustees and beneficiaries.

- 3345(b) – “Beneficiary Well-Being Program”: This section defines what a well-being program means, which includes “seminars, courses, programs, workshops, counselors, personal coaches, short-term university programs, group or 1-on-1 meetings, counseling, family meetings, family retreats, family reunions, and custom programs, all of which having 1 or more of the following purposes:

(1) To prepare each generation of beneficiaries for inheriting wealth by providing the beneficiaries with multigenerational estate and asset planning, assistance with navigating intergenerational asset transfers, developing wealth management and money skills, financial literacy and acumen, business fundamentals, entrepreneurship, knowledge of family businesses, and philanthropy.

(2) Educating beneficiaries about their family history, the family’s values, family governance, family dynamics, family mental health and well-being, and connection among family members.”

- 3345(c) – Increased Trustee Discretion and Beneficiary Rights: The Trustees of a BWT must provide the beneficiaries, individually, and as a group, with “beneficiary well-being programs” at such times and in such a manner as provided in the trust agreement, or, if not in the trust agreement, as the Trustee determines in his or her discretion. So, the beneficiaries of a BWT have the right to receive these beneficiary well-being programs as a part of their bundle of rights and interests as a beneficiary of the trust.

- 3345(d) – Well-Being Programs are a Trust Expense:

(1) Well-being programs are an expense of the administration of the trust.

(2) Trustees can run the beneficiary well-being programs or hire others.

(3) Each provider of beneficiary well-being programs is entitled to payment. The Trustee is entitled to the full fiduciary compensation to which the Trustee is otherwise entitled as Trustee without a reduction for the fees and costs associated with the well-being program. These fee provisions will make it easier and more compelling for a Trustee to provide well-being programs to beneficiaries proactively and liberally.

- 3345(e) – Expanding the Scope: This section further expands the scope of the well-being programs by allowing the governing instrument to provide for additional powers and rights. This means is that the Settlors and drafters are free to work together to really tailor the well-being provisions to the Settlor’s objectives.

Practice Considerations – Implications for Estate Planning:

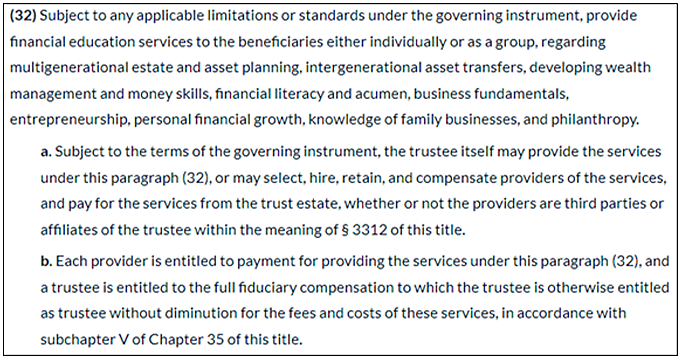

- In 2024, Delaware also added the following excerpted new power to Delaware’s Trustee Powers[2]:

- Trustees Discretion and Fiduciary Duties

- Increased Responsibilities and Trustee Discretion: Grants Trustees broad discretion in determining what best serves the beneficiary’s well-being.

- Balance: Trustees must balance their fiduciary duty to preserve trust assets with their obligation to enhance the beneficiary’s quality of life.

- Risk of Trustee Overreach: The wide discretion afforded to Trustees raises concerns about potential overreach or misuse of powers.

- Difficulty in Judicial Review: Since the statute allows Trustees to make subjective decisions about a beneficiary’s well-being, courts may find it difficult to review Trustee actions.

Estate of Williams [3]: Omission of a Testator’s Other Known Children Demonstrated His Intent to Exclude All Preexisting Children, Known or Unknown.

Background: Williams fathered seven children, five of whom were born out of wedlock and two of whom were the result of a marriage. Williams knew of the existence of all of his children, except for Carla (one of his five children born out of wedlock). Williams executed a trust in which he only named the two children of his marriage as the beneficiaries. After Williams’s death, Carla, who discovered her half-siblings after taking a DNA test, received notification of the administration of Williams’s estate, and she petitioned to receive a share of his estate as an omitted child. The trust did not contain a general disinheritance clause.

Holding and Analysis: The trial court held in favor of the named beneficiary children and found that Carla failed to establish that the reason Williams did not provide for her was “solely” because he was unaware of her birth. The Appellate Court affirmed and determined that a child born before execution of a testamentary instrument is presumed to be intentionally omitted, unless:

(1) the child shows that the testator was unaware of the child’s birth; and

(2) that the child was not provided for solely due to that unawareness.

In this case, Williams’s failure to provide anything to four of his known children evidenced an intent to provide only for the two children of his marriage, whom he named as beneficiaries. It should also be noted that a general disinheritance clause is one (but not the only) method to demonstrate a decedent’s intent to omit unknown heirs. Therefore, a general disinheritance is not an additional element required to prove that Carla was not provided for solely due to that unawareness.

Estate of Nowell v. Commissioner [4]: Fractional Interest Discount Planning with QTIPS

Questions Presented

- Fractional Interest Discount: Whether certain partnership interests includable in the gross estate pursuant to § 2044 should be merged with the partnership interests includable in the gross estate pursuant to § 2038, for valuation purposes.

- Valuing Partnership Interests as an “Assignee” or “Partnership Interest”: Whether the interests in two partnerships passing at death should be valued for federal estate tax purposes as “Assignee Interests” or as “Partnership Interests.”

Background

During their marriage, Mr. and Mrs. Nowell (residents of Arizona – a community property state) acquired various securities and real estate. On April 20, 1990, Mr. and Mrs. Nowell established their revocable trusts (the “A.L. Nowell Trust” and the “Ethel S. Nowell Revocable Trust”) and funded them with their community property. Each of their revocable trusts named their daughter, Nancy, and son-in-law, David, as the remainder beneficiaries.

Six days later, Mr. Nowell died. His trust property was transferred into three separate trusts: (1) GST Exempt QTIP, (2) GST Non-Exempt QTIP and (3) a trust titled “The Decedent’s Trust.” Each trust named Mrs. Nowell and David as co-Trustees. Mr. Nowell’s Executors made a QTIP election and claimed a marital deduction, which was allowed for federal estate tax purposes.

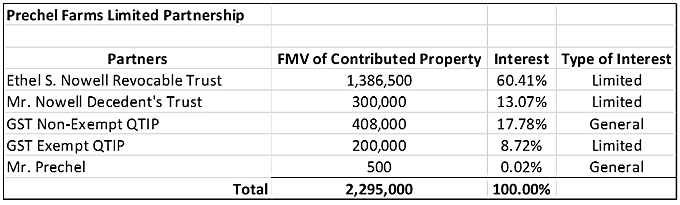

In 1991, Mrs. Nowell and David formed two limited partnerships, Prechel Farms Limited Partnership (“PFLP”) and the ESN Group Limited Partnership (“ESN”). Both of which were funded using the assets of Mrs. Nowell’s revocable trust, the QTIP trusts and The Decedent’s Trust, as well as a $500 contribution from David. The partnership agreements for both entities provided that no assignee of a limited partnership interest would become a limited partner unless the general partners consented to the assignee’s admission as a limited partner.

The following charts display the pre-discounted value of property contributed:

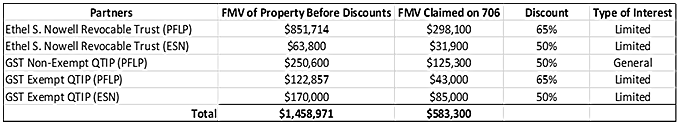

Mrs. Nowell died in 1992. Under the terms of the various trust agreements, the 99.98% interest in PFLP not owned by David passed to him and all interests in the ESN passed to Nancy. The value of these transfers was discounted at either 50% or 65% on Mrs. Nowell’s estate tax return to account for lack of control and lack of marketability.

The chart below lists the values reported on Mrs. Nowell’s 706 and the discounts applied:

Holding & Analysis

Issue 1: No Merger of Interests

The court held that Mrs. Nowell’s partnership interests that were held by her revocable trust and the QTIP trusts for her benefit, should be valued separately and should not be merged for valuation purposes, thereby allowing the fractional interest discounts. The court stated that property in a QTIP trust does not actually pass to or from the second decedent. At no time does the second decedent control or have power of distribution over the shares held in a QTIP trust. § 2044 only requires that the QTIP property be included in the estate, at its fair market value, for purposes of determining the transfer tax. It does not require, however, that the decedent aggregate QTIP assets with other assets owned at death.

Therefore, a family may transfer property to various trusts and then claim that the total value of all trusts is worth less than the value of the underlying property because each trust owns only a partial share of the property. This is true even when the family still owns and controls the trusts and, therefore, owns and controls all the property.

Issue 2: “Assignee” or “Partnership Interest”

In addressing the second issue, the court looked at the transfer of both general and limited partnership interests and afforded each a different treatment based on specific language in the partnership agreements. Under the agreements, if the assignee of a general partnership interest is a general partner at the time of such assignment, the assignee is automatically a general partner. Furthermore, an assignee of a limited partnership interest could not become a limited partner unless all general partners consented to the assignee’s admission as a limited partner. The IRS argued that the limited partnership limitation should be disregarded because Nancy and David, as assignees, held 100% of the general partnership interests and, therefore, could admit themselves as limited partners.

However, the court refused to consider the interests held by Nancy and David after Mrs. Nowell’s death and held that it must apply the objective standard of a hypothetical buyer and seller to determine if the general partners would elect to admit the heirs as new partners, rather than the actual facts. Therefore, the limited partnership interests transferred to Nancy and David were assignee interests and should be valued as such, rather than as partnership interests.

The court came to a different conclusion for the general partnership interest. At Mrs. Nowell’s death, David inherited another 17.78 % of this general partnership interest, the rights of which were unrestricted under the partnership agreement. Without the approval requirements associated with the limited partnership interests, the general partnership interest automatically treated the beneficiary as a partner. Therefore, the court held that the transfer of a general partnership interest should be valued as a full partnership interest and the valuation discount should be reduced.

McDougall v. Commissioner [5]: Termination of QTIP Trust Results in Gift Tax Liability to Remainder Beneficiaries

Background

Mrs. McDougall (the “Decedent”) died in 2011, survived by her husband, Bruce, and their two adult children, Linda and Peter. The Decedent’s gross estate was valued at approximately $60 million. Under the Decedent’s Will, she left the residue of her estate to a residuary marital trust (the “Residuary Trust”) in which Bruce had an income interest, and Linda and Peter, had remainder interests. A QTIP election was made on the Decedent’s estate tax return with respect to the property that funded the Residuary Trust and claimed a $54 million marital deduction.

Bruce was the Trustee of the Residuary Trust, which provided for annual income distributions to Bruce, and principal distributions for HEMS. The Decedent’s Will granted Bruce a limited power to appoint the principal of the Residuary Trust “to or among the Decedent’s descendants…outright or in trust, on such terms and in such amounts as he shall determine.” By 2016, the value of the assets in the Residuary Trust had more than doubled. Bruce, Linda, and Peter agreed that those assets could be more effectively used if Bruce held them outright and free of trust. Later that year, Bruce, Linda, and Peter entered into a nonjudicial agreement (the “Agreement”) whereby the parties agreed to terminate the Residuary Trust, distribute its assets outright to Bruce, then Bruce would sell those assets to a trust benefiting Peter, Linda and their descendants (the “Descendant’s Trust”) in exchange for promissory notes of equal value.

Bruce, Linda and Peter each separately filed gift tax returns for 2016 and reported that the transactions above resulted in offsetting reciprocal gifts and no gift tax. The IRS examined the gift tax returns and issued a notice of deficiency to Bruce, Linda and Peter stating that (1) the commutation of the Residuary Trust resulted in gifts from Bruce to his children under § 2519 and (2) the agreement resulted in gifts from the children to Bruce of the remainder interests in the Residuary Trust under § 2511.

Holding & Analysis

Ultimately, the Tax Court held that no taxable gift by Bruce resulted from (1) the termination and distribution of the Residuary Trust assets to Bruce, or (2) the transfer of those assets to the Descendant’s Trust (assuming that the value of the assets and the promissory notes were of equivalent value). However, the agreement to terminate the Residuary Trust resulted in gifts to Bruce by Linda and Peter under § 2511.

Terminating the QTIP Trust Was Not a Gift from Bruce to His Children

The termination of the Residuary Trust did not result in a gift from Bruce to Linda and Peter. The court faced this same question in the Estate of Anenberg and using it as precedent, held that the termination of the trusts through which Bruce held his qualifying income interest in the Residuary Trust and the distribution of the Residuary Trust to Bruce was a disposition within the meaning of § 2519(a). However, a transfer alone is insufficient to create a gift tax liability, as there must be a gratuitous transfer. In this case, there was no gratuitous transfer because Bruce would be in the same position if the property of the trust had been distributed outright to him at his wife’s death rather than to the QTIP trust.

Linda and Peter Made a Gift to Bruce

To determine whether a gratuitous transfer occurred, the court compares what each party had before and after the transaction. Under the “gratuitous transfer” framework described in Anenberg, Linda and Peter plainly made gratuitous transfers. Before the implementation of the Agreement, Linda and Peter held valuable rights (i.e., the remainder interests in the QTIP property). After the implementation of the Agreement (which required their consent) Linda and Peter had given up those valuable rights by agreeing that all of the assets of the Residuary Trust would be transferred to Bruce, and they received nothing in return. By giving up something for nothing, Linda and Peter engaged in gratuitous transfers, which are subject to gift tax under §§ 2501 and 2511.

The Issue of Valuing the Gift

The court did not opine on the value of the gifts. However, the fair market value of the gift is the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller. If the Residuary Trust was a unitrust, the valuation question would be rather straightforward (and potentially devastating due to the size of the trust at over $100 million). Luckily for the children, their remainder interest could be reduced by additional distributions of principal and are subject to complete divestment through Bruce’s exercise of a testamentary power of appointment.

Estate of Fields v. Commissioner [6]: Inclusion of Transferred Assets under § 2036(a)

Questions Presented

- Inclusion of Transferred Assets: Whether § 2036(a) requires including the full value of the assets transferred to a limited partnership in the estate when the decedent retained economic benefits.

- Accuracy-Related Penalty: Whether the Estate is liable for an accuracy-related penalty under § 6662(a) and (b)(1).

Background

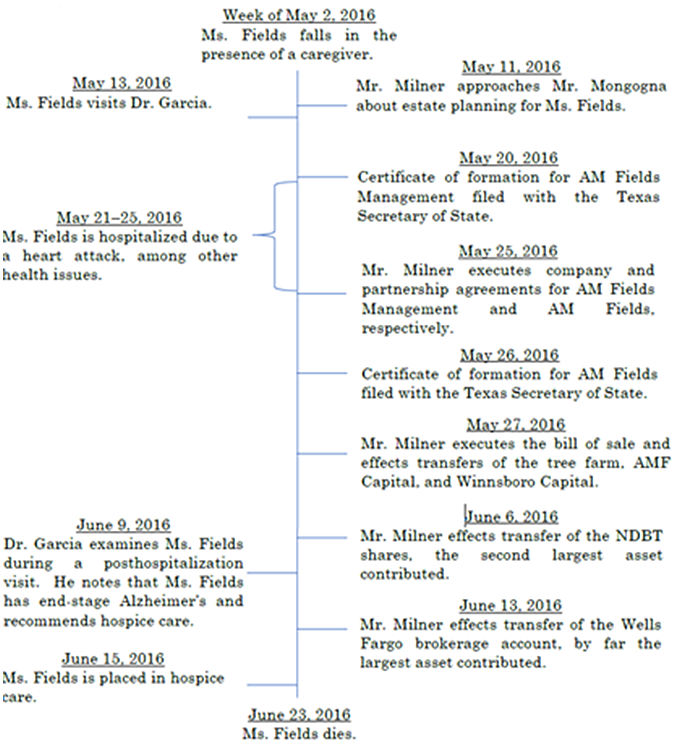

This case arises from an estate plan that Mr. Bryan Milner (the Decedent’s nephew, “Bryan”) implemented for Ms. Anne Milner Fields (the “Decedent”) a month before her death on June 23, 2016, using the Decedent’s validly executed power of attorney naming him as attorney-in-fact.

The Decedent was a successful businesswoman, and she had a very close relationship with Bryan. In 2010, the Decedent validly executed a Will and a power of attorney, naming Bryan as Executor and her attorney-in-fact. The Decedent’s Will provided for eleven specific bequests and left the remainder of the estate to Bryan. In 2012, the Decedent’s physician determined that she could no longer make her own financial decisions, so Bryan began handling her financial affairs.

The timeline below outlines the events that took place in May 2016 through June 2016.

On May 20, 2016, Bryan formed AM Fields Management, LLC (“AM Fields Management”), of which he was the sole Member and Manager. He then formed AM Fields, LP (“AM Fields”) on May 26, 2016, for which AM Fields Management was the general partner and the Decedent was the limited partner. In forming AM Fields, Bryan acted on behalf of both the general and limited partners, as he signed the partnership agreement as himself and as the Decedent’s agent.

Using the power of attorney, Bryan transferred to AM Fields approximately $17 million of the Decedent’s personal assets (constituting most of her wealth). He also caused AM Fields Management to contribute $1,000 to AM Fields. In exchange, the Decedent received a 99.9941% limited partner interest in AM Fields, and AM Fields Management received a 0.0059% general partnership interest.

After the Decedent died, Bryan appraised the Decedent’s limited partner interest in AM Fields. The appraised value as of the Decedent’s date of death was $10.8 million, which reflected the approximately $17 million in contributed assets less a 15% discount for lack of control and a 25% discount for lack of marketability. Bryan, as Executor, reported this discounted value on the Estate’s federal estate tax return.

The IRS audited the return and issued a Notice of Deficiency stating that § 2036(a) applies such that the gross estate includes the full date-of-death value of the Decedent’s assets that were contributed to AM Fields. The IRS also issued a penalty under § 6662(a) and (b)(1) for an underpayment attributable to negligence.

Holding & Analysis

Inclusion of Transferred Assets under § 2036(a)

There are three requirements for property to be included in the gross estate under § 2036(a):

(1) Decedent made an inter vivos transfer of property;

(2) Decedent retained an interest or a right specified in § 2036(a)(1) or (2) in the transferred property that he or she did not relinquish until death; and

(3) The transfer must not have been a bona fide sale for adequate and full consideration.

The first requirement was satisfied since Bryan, on behalf of the Decedent, transferred five of the Decedent’s assets to AM Fields.

- Whether the Decedent Retained Rights or Interests in the Transferred Property

The court held that the Decedent retained the right to income from the transferred assets, as well as control over partnership distributions through Bryan, her agent and the partnership’s general manager. This meant that despite the transfer, the Decedent had not relinquished economic enjoyment of the assets. Although the partnership agreement gave AM Fields Management some rights to the income and underlying property of AM Fields, it acquired those rights in exchange for a mere $1,000 contribution and its interest in the limited partnership was de minimis.

Furthermore, the court determined that the Decedent retained enjoyment (i.e., substantial present economic benefit) of the transferred assets. The AM Fields transfers left the Decedent with only $2 million of assets outside the partnership, while her Will listed bequests of $1.5 million and a foreseeable substantial estate tax liability. On this basis, the court found an implicit agreement between Bryan and the Decedent that he would make distributions from the partnership to satisfy her expenses, which he eventually did to satisfy the Decedent’s bequests and the estate tax liability. The use of a significant portion of partnership assets to discharge obligations of the Decedent’s estate is evidence of a retained interest in the assets transferred to the partnership. § 2036(a)(2) also applies, as Section 13.1(a) of the partnership agreement provided that the Decedent had the right, in conjunction with Bryan, to dissolve the partnership, upon which Bryan would be obligated to liquidate the property and pay off partnership debts and distribute cash to the partners.

Therefore, the Decedent retained the right—in conjunction with Bryan—to at any time acquire outright all income from the transferred assets and then designate its disposition. The court also emphasized that there was essentially no pooling of assets in the partnership, which did not function as a joint investment vehicle, but rather only as a vehicle to reduce estate tax.

- The Transfer Was Not a Bona Fide Sale

The court held that the Decedent did receive adequate and full consideration. However, the transfer was not considered a “bona fide” sale because there was no legitimate non-tax purpose for the transfer. The court rejected the Estate’s claims that the partnership was formed for asset management and protection from elder abuse, finding these reasons unsupported by the facts. In reviewing the facts, the court focused on many factors including: (a) the age and health of the Decedent at the time of the contributions, (b) the fact that no discussions of transferring the Decedent assets into a partnership took place until the Decedent’s health declined, (c) no pooling of assets for a joint enterprise and (d) the assets transferred depleted nearly all the Decedent’s liquidity where the Estate could not pay the bequests or estate tax liability.

Accuracy-Related Penalty

The Estate was held liable for an accuracy-related penalty under § 6662(a) for underreporting the estate tax liability. The court found that the Estate did not have reasonable cause for an underpayment, and it did not rely on competent professional advice in excluding the full value of the assets from the gross estate.

Specifically, Bryan never contended that he personally considered, researched, or understood the implications of § 2036 for the Estate’s estate tax liability. Moreover, the court held that “a reduction of approximately $6.2 million in the Estate’s reportable assets thanks to the seemingly inconsequential interposition of a limited partner interest between the Decedent and her assets on the eve of her death would strike a reasonable person in Bryan’s position as very possibly too good to be true.” Furthermore, the court noted that there was no evidence that the accountant for the Estate advised Bryan that the Estate could both report the value of the Decedent’s AM Fields interest at a discount and also exclude the entire value of the AM Fields assets.

_______________

[1] 12 Del. C. § 3345.

[2] 12 Del. C. § 3325(32).

[3] Estate of Williams, 104 Cal. App. 5th 374 (2024).

[4] Estate of Nowell v. Commissioner, No. 19056-96, 1999 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 15 (T.C. Jan. 26, 1999).

[5] McDougall v. Commissioner, 2024 U.S. Tax Ct. LEXIS 2281 (T.C. Sep. 17, 2024).

[6] Estate of Anne Milner Fields v. Commissioner, No. 1285-20, 2024 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 92 (T.C. Sep. 26, 2024).